I am looking at thick, heavy reports, conference papers, sequential journals and newsletters, printouts, folders with copies of significant documents - all with a thin film of dust - and most destined for the recycle bin. Midwifery, lactation, College of Midwives, Nurses Board of Victoria, and lots more. I can't possibly transplant the contents of this room to my new home. Retirement means down-sizing.

I tell myself it's silly to grieve about throwing out material that has no relevance. I remind myself that I haven't opened or looked at most of these documents in years - and I'm not likely to, in the next decade. But I am grieving.

|

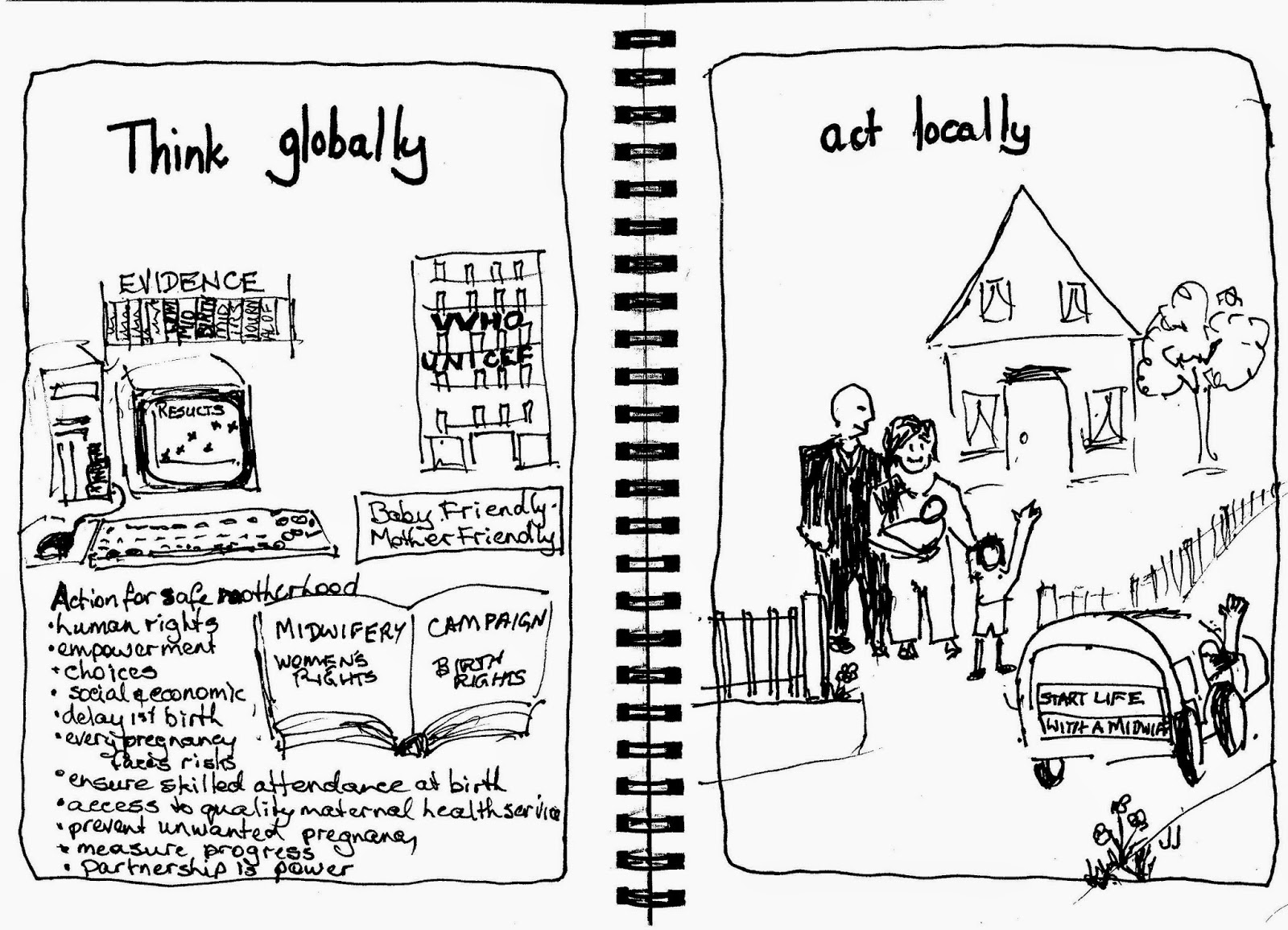

| Think globally, act locally (click to enlarge) |

Thinking globally, acting locally

The global terrain of midwifery knowledge in the 1990s nurtured my hungry mind. I was fortunate to be able to integrate theory and evidence, and apply it from first principles to childbirth and breastfeeding in my own community.

The information age took us from paper to digital communication. I learnt 'mail merge' to produce addresses printed out on sticky-labels. Documents and letters were photo-copied and physically mailed out; faxes and overhead transparencies were the mainstay for teaching and disseminating information within professional circles. These were quickly replaced with email, websites, data projectors, and much much more.

This is my thumbnail sketch of significant midwifery moments from my perspective. (Readers can use search engines to check details and fill many of the gaps that my imperfect memory will undoubtedly produce!)

World Health Organisation had, in 1985, published the Fortelesa Declaration on appropriate use of technology in birth, followed in the 1990s by Safe Motherhood publications, such as Care in Normal Birth, a practical guide (1996). Parallel was the WHO-Unicef Innocenti Declaration leading to the Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative, placing emphasis on the protection, promotion and support of breastfeeding as a priority for all babies.

Coming as I did at the time from my own childbearing and breastfeeding years, I was ready to integrate the science (global) with the practice (local). My husband, Noel, had researched the protective effect of colostrum on the newborn calf and been awarded Masters and PhD degrees for his research in the 1970s. The literature review included current scientific knowledge on human colostrum and breastfeeding, and the emerging devastating impact of the loss of reliance on breastfeeding, particularly in poorer communities. My understanding of the finely tuned natural phenomena in childbearing and nurture heightened my commitment to working in harmony with natural processes.

In those days, many mothers received repeated doses of the synthetic narcotic Pethidine (also known as meperidine or Demarol) in labour, and their babies were born unable to achieve the most basic of physical challenges - effective breastfeeding - and often ingested little or no colostrum. Babies were separated from their mothers, given dummies (pacifiers) to keep them quiet, nursery care, sterile water, and 'white water' (code for formula - administered with bottle and teat, of course) to give the mother a good night's sleep (with the aid of a sleeping pill). Nipples were often severely damaged. Breast engorgement followed: painful, hard and unproductive breasts that quickly progressed to mastitis.

Embedded in the maternity reform agenda of the late 1990s was the development of women's rights in childbirth. Midwifery, as a profession, could not insist that mothers accept an ideal of umnedicated, natural labour, and the constant commitment of exclusive breastfeeding for six months, with continuing breastfeeding to the age of two years and beyond - unless women, MOTHERS, agreed that this was indeed the best pathway for them and their babies.

The notion of women's rights in childbirth has simmered away without, in my mind, reaching any major breakthroughs. A competent adult does have the right to refuse any medical treatment. This ought to be a real winner for women in maternity care, because the fact is that for most women, pregnancy, birth, and the baby's establishment of breastfeeding are able to happen without any outside intervention or assistance. On the contrary, the principle of non-intervention in such normal physiological processes is actually established as the optimal.

'Unassisted' childbirth is usually good. From a midwife's point of view it's the gold standard for unmedicated, spontaneous birth. When a midwife completes the statistics form for a birth we check 'unassisted' if the mother pushed the baby out herself.

The professional midwife who is in attendance does not necessarily assist. I think it's Michel Odent who said (I don't have the reference) that "One cannot actively help a woman to give birth. The goal is to avoid disturbing her unnecessarily."

Yet too many women today, and 10 years ago, and 20 years ago, will tell you they experienced bullying and coercion in maternity care; that they were told "You must have an induction of labour ..." "You must have a caesarean ...." "Your baby must have this artificial formula milk ..." It is, and always has been, rare if not unheard of in mainstream maternity services for women to be presented with information and support to make the decision they believe is best for them. Maternity professionals have learnt, often without consciously recognising it, how to leave a woman no alternative. "Your baby will die if we don't ..."

Having considered women's rights in childbirth from many perspectives, research, and practice, the only way I can see to reduce the incidence of birth trauma is through expert midwifery practice, together with effective support of women in decision making. A woman who is working within a reciprocal partnership with a known midwife; a woman who understands the unique and awesome natural processes in the whole birthing-bonding continuum; this woman and her midwife will do all she can to stick with 'Plan A'. Plans B and even Plan C are available, because medicine and surgery have advanced to the point where there are very few unpredictable situations in which the woman's life, or her baby's life, are truly at risk.

In the past decade I have witnessed the growth of intentionally unattended childbirth, also known as freebirth. We don't know how many babies are born this way, because some are recorded as 'BBA' (born before arrival). Some 'freebirths' happen under the watchful eye of unqualified people, including doulas, who probably do not have the knowledge or skill to intervene when even the most common complications arise. I think this is a tragic development, because I see the role of the midwife as being so basic.

I say this with deep respect for those who have experienced unwanted interference in their birthing processes. I am horrified that women are giving up the fight too early, and not exercising their right to decline treatment. Others are being swept into an idealism about unassisted, undisturbed birth that they will probably regret later.

Women and babies will die in free birthing. This is unacceptable. Our bodies are wonderfully made, and science as well as experience have taught us about oxytocin and bonding. If that were the end of the story there would be no need for the professional midwife or anyone else. We could just hide in our undisturbed cave and birth our babies in blissful ignorance.

Women's rights in birth must come down to principles of safety and access to appropriate interventions in a timely manner.

The principle that I follow is that there must be a valid reason to interfere with the natural process (WHO Care in Normal Birth 1996) We cannot know ahead of time if a complication (ie valid reason) may arise, even in the least risky situation. If a woman is giving birth unattended she has no idea if she is progressing normally, or not. She needs to minimise neocortical activity as the labour progresses, which means she must stop analysing and assessing what's happening.

That's the midwife's job.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Thankyou for your comments, which will appear after being checked by the moderators of this site.